The Double Helix of the American Soul——From Puritan Covenant to Frontier Sovereignty

(Chapter 12 Summary & Conclusion in the book American Rednecks)

John J. Lee, PhD

A Geological Fault Line Through American History The story of the United States is not a harmonious symphony but rather a fugue, filled with inherent contradictions and dissonant chords. Its core driving force originates from a profound and almost irreconcilable geological fault line that runs through its history. This fault line separates two distinct worldviews, two fundamental definitions of liberty and authority, and two irreconcilable "first principles." These two principles, like a double helix wound around America's DNA, are the "Social Contract," derived from the New England Puritans, and "Individual Sovereignty," born from the Scots-Irish of the Appalachian frontier.

The central argument of this thesis is that the profound schisms in contemporary American society—be it political polarization, cultural wars, or fundamental disputes over "fairness" and "justice" are not recent phenomena. They are the inevitable result of a relentless, two-and-a-half-century struggle between these two deep-seated cultural genes. The "Redneck," as a sociological and cultural archetype, is the most steadfast and enduring historical carrier of the "Individual Sovereignty" principle.

Their story is an epic of paradoxes: They were the founders of the republic, yet they have always existed in a state of tension with the state apparatus they helped create. They were the vanguard of the nation's westward expansion, yet they became victims of capital's expansion. They were the builders of industrial miracles, yet they were discarded by the tides of technological progress. They constructed the infrastructure of modern cities, yet they have always been excluded from the centers of power and wealth.

For 250 years, this history has forged a unique cultural psychology: extreme individualism, a deep-seated distrust of external authority, a fierce anti-elitism, a devotion to traditional values, and a profound sense of historical betrayal.

The rise of Donald Trump was not a historical accident but a violent earthquake along this geological fault line, triggered by the immense pressures of globalization, digitization, and multiculturalism. With his uncanny intuition, he precisely touched the collective trauma of this

forgotten group. His anti-establishment posture, his rejection of globalization, and his promise to "Make America Great Again" were not political strategies but a cultural summons. The support for him was not a simple political choice but the culmination of generations of economic anxiety and cultural resentment. This thesis will systematically trace the continuous collision of these two "first principles" at several key junctures in American history—the Revolutionary War, the Westward Expansion, industrialization, political realignment, and the era of globalization.

By dissecting the fundamental differences between the two sides on core concepts like liberty, land, and fairness, this paper aims to reveal that America's current crisis is not a simple dispute over policy but a profound philosophical conflicts. Understanding this history, interwoven with glory and rage, is not only the key to deciphering the Trump phenomenon but also the only way to confront the deep fissures in the American soul and to question whether the republic's collective identity can still be sustained.

Chapter I: The Establishment and the Anti-Establishment

To understand the internal conflicts of any civilization, one must trace its original creation myths. The uniqueness of the United States lies in its possession of two parallel and contradictory creation myths, which have respectively shaped the cultural archetypes of the "Establishment" and the "Anti-Establishment." This is not merely a political division but a philosophical schism born from vastly different experiences of survival.

The Genesis of the Establishment Spirit:

The Puritan "City upon a Hill" and the Covenant of Order: The philosophical cornerstone of the American Establishment was laid by the 17th-century Puritans who arrived at Plymouth Rock aboard the Mayflower. They crossed the ocean not in pursuit of unrestrained individual liberation but to establish a community guided by God's will and filled with moral order: a "City upon a Hill," to serve as a model for a fallen world. The famous Mayflower Compact is the perfect embodiment of this spirit. In a wilderness devoid of a monarch, a church, and an authority vacuum, they pledged to create "just and equal laws" and swore to "all due submission and obedience." It established a core belief in American culture: legitimate authority derives from the consent of the governed, and liberty is realized within the framework of law and order. This reverence for order, covenant, collective responsibility, and the rule of law was deeply rooted in New England's soil. While it rejected the divine right of kings of the Old World, its core remained an aspiration for an orderly, virtuous, and purposeful collective enterprise.

The Injection of the Anti-Establishment Spirit:

The Scots-Irish Frontier Logic and Individual Sovereignty. However, nearly a century after the Puritans established their orderly colonies, a radically different cultural torrent surged into the North American continent in the early 18th century, completely altering America's character.

These were the Scots-Irish, a resilient and battle-hardened people forged on the anvil of history. They were 17th-century Presbyterian Protestants who had migrated from the Scottish Lowlands to the Ulster province in northern Ireland. In Ireland, they were caught in a double bind: Oppressed by the official Anglican Church of England and in constant conflict with the conquered native Irish Catholics. For a century, they lived in an environment without reliable authority, where survival depended on their own strength and clan solidarity. This experience instilled in them a deep-seated, almost instinctual suspicion and hostility toward any form of centralized government, entrenched aristocracy, and official church. When they migrated to America in large numbers due to economic and religious oppression, they found that earlier English and German immigrants had already occupied the fertile lands of the East Coast.

They were forced to move inland, following the Great Wagon Road into the rugged backcountry of the Appalachian Mountains. In this wilderness, beyond the reach of law and civilization, they finally found their spiritual home. Here, the laws of survival were simplified to their most primitive core: individual prowess, clan-like loyalty, and the long rifle in their hands. They forged a unique "frontier ethic": land did not belong to absentee landlords with distant government-issued deeds but to those who cultivated and defended it with their own blood and sweat (the "squatter" logic); a distant government was good for nothing but collecting taxes and restricting their freedom; justice was not delivered by a judge's verdict but by "blood for blood" within the community. This defiant, fiercely independent, and anti-authoritarian individualism became the unyielding core of the American Anti-Establishment spirit.

This duality of the Establishment and the Anti-Establishment is both the source of America's profound social divisions and the engine of its vitality and innovation. The constant challenge from the Anti-Establishment serves as a check on government overreach and a counterweight to elite power, driving societal self-correction. The Establishment framework, in turn, provides the legal, institutional, and social capital necessary for the nation's survival. It is the persistent tension between these two archetypes, rather than simple opposition, that constitutes the most dynamic energy in the American spirit.

Chapter II: The Clash of Two Visions of Liberty

The American Revolution is often portrayed as an external conflict of a colony against its metropole, but its deeper essence was a profound internal clash between two irreconcilable conceptions of "liberty." The protagonists of this clash were the East Coast Founding Elites, who believed in the "Social Contract," and the Appalachian frontiersmen, who championed "Individual Sovereignty." This was a constitutional liberty, centered on the principle of "no taxation without representation," the sanctity of property rights, opposition to the arbitrary taxation of a despotic monarch, and the establishment of a representative government bound by law. When they protested against acts like the Stamp Act, their weapons were legal debates, pamphlets, and trade boycotts. They sought a struggle for rights within the existing legal framework.

However, on the other side of the Appalachian Mountains, the frontiersmen were already waging another war with their long rifles and tomahawks. Long before the Stamp Act was enacted, the British government's Proclamation of 1763 had ignited their fury. To pacify the Indian tribes, the proclamation forbade the colonists from expanding west of the Appalachian Mountains. For the people of the frontier, this was not an abstract legal issue but a direct deprivation of their right to exist. They were not defending the abstract "natural rights" of Locke's writings but a more primitive and concrete "liberty of natural man"—the absolute right to self-governance, free from any external authority, whether it be the king in London or the congress in Philadelphia. They believed that the western lands were a promised land given to them by God, and no government had the right to stop them from possessing it.

After the war broke out, these frontier militias became some of the most determined and formidable fighting forces of the Continental Army. They wore no uniforms, did not march in formation, and fought the British using guerrilla tactics similar to those of the Indians, playing a decisive role, especially in the southern theater.

The famous Battle of Kings Mountain was a classic frontier war. When a British general threatened to sweep through the mountains with "fire and sword," thousands of "overmountain men" spontaneously assembled, launching a lightning-fast raid that annihilated the Loyalist forces, dealing a severe blow to Britain's "Southern Strategy" and marking a turning point in the Revolutionary War. However, the war's aftermath dramatically exposed this internal conflict.

As the Founding Elites in Philadelphia drafted a constitution aimed at establishing a strong federal government, the people of the frontier were horrified to discover that they had merely traded a distant oppressor in London for a new one close at hand. The federal government's tax on whiskey, levied to pay off war debts, struck at the economic lifeblood of the frontier farmers. In the currency-scarce backcountry, whiskey was not just a drink but a common medium of exchange.

This sparked the famous Whiskey Rebellion. In the end, President George Washington himself led federal troops to crush the uprising. This scene was highly symbolic: comrades-in-arms who had once fought side by side now faced each other in battle. It profoundly revealed the fracture lines within the nascent republic. The frontiersmen were heroes of the American Revolution, but the radical, individualistic liberty they championed was fundamentally incompatible with the centralized, Hamiltonian vision for a modern nation that required a strong central government and unified taxation. They thus became, and would remain, the country's permanent "Internal Other." This was the first armed confrontation between the constitutional liberty of the "Social Contract" and the natural liberty of "Individual Sovereignty," and the echoes of this clash still reverberate in American politics today.

Chapter III: The Conflict of Two Views of Land Ownership: "Tomahawk Rights" Versus "Parchment"

The most tangible and substantial reward of the Revolutionary War was land. After the war, with the confiscation of Loyalist and British Crown lands and the opening of western territories, a massive redistribution of land gave rise to an agrarian economy centered on small-holding farmers, which became the social cornerstone of the Jeffersonian republic ideal. However, this process was once again fraught with fierce conflict between the "customary law" of the frontier and the "statutory law" of the federal government, centered on two fundamentally different understandings of land ownership.

On the frontier, the logic of land ownership was brutally simple: "Tomahawk Rights." A pioneer would enter an uninhabited area, mark a tree with his tomahawk, build a simple log cabin, and clear a small patch of cornfield, and the land would "naturally" belong to him. This logic completely disregarded legal procedures but was widely accepted as "customary law" in frontier communities. The philosophy behind it was the most primitive version of Locke's labor theory of value: whoever mixes their labor with the land has the right to own it. This method was also "effective" in seizing land from the Indian tribes.

However, for the Establishment elites of the East Coast, this chaotic form of possession was an obstacle to national development. The new federal government's Land Ordinance of 1785 sought to replace the frontier's law of the jungle with the rationality of modern engineering science. The ordinance divided the western lands into a neat grid of six-square-mile townships, which were systematically surveyed and then sold in parcels at public auction, with ownership confirmed by a government-issued "parchment" deed.

The conflict between these two systems was inevitable. The axe and the long rifle backed the "customary law" of the frontier, but in the federal legal system, this possession based on "customary law" was often no match for a legal challenge based on a written deed and represented by a lawyer. Countless pioneers found that the homesteads they had painstakingly cultivated and even shed blood to defend were legally taken away overnight by an eastern land speculator holding a piece of "parchment." The result was that land held by "customary law" was swallowed up, piece by piece, by "statutory law." This again intensified the conflict between the frontiersmen, the eastern elites, and the federal government. In their view, the law and the courts were not impartial arbiters but tools for the rich to plunder the labor of the poor. They felt betrayed once again: they had won the land for the nation, only to be dispossessed again in the new order. This deep distrust of the legal system and financial capital became an indelible part of the "Redneck" cultural DNA.

Chapter IV: The Westward Expansion—A Conquest That Sowed Cultural Genes

The 19th-century American Westward Expansion is often portrayed as a geographical conquest and territorial expansion that manifested the nation's "Manifest Destiny." However, this epic migration was, more profoundly, a crucible of cultural reforging and a reshaping of the American spirit. It sowed cultural seeds across the vast new continent that continue to profoundly influence American society today, with the pioneers, largely of the "Redneck" cultural archetype, serving as the "foot soldiers" of this great sowing.

These pioneers, driven by the Jeffersonian ideal of the independent "yeoman farmer," participated in the displacement of Native American and Hispanic populations, believing they could create their own paradise in the new West. They were the heroes of the nation's territorial expansion, merging their personal desire for land with the grand national narrative. However, they soon discovered that their true adversary was not the harsh wilderness and the Indians' arrows but the more powerful and intangible forces of emerging industrial capitalism. The railroad companies, as "iron monsters," used their monopolistic power to set exorbitant shipping rates, devouring the meager profits of the farmers. Eastern bankers, through high-interest loans, trapped countless pioneers in a cycle of debt, where a natural disaster or market fluctuation was enough to make them lose everything. The federal government's land policies failed to benefit the masses as advertised, instead colluding with large speculators and corporations to relentlessly exploit the labor of pioneers through high-priced auctions and harsh taxes. The West did not become a utopia of individual opportunity but quickly devolved into a "capital colony" controlled by distant financial and corporate elites. This huge chasm between ideal and reality instilled in the pioneers a sense of betrayal even more profound than what they had felt in Appalachia. This feeling, combined with the unique violent environment of the frontier, eventually solidified into a distinct cultural DNA:

1. Extreme Hostility to Central Authority: The pioneers believed they were used and betrayed by the distant elites in Washington and Wall Street. This belief intensified their distrust and hostility toward all forms of central authority, whether it be the government or large corporations. This anti-establishment, anti-elite populist mindset became the political bedrock of the vast "Redneck" regions of the Midwest and South.

2. A Deep-Rooted Gun Culture: In an environment lacking effective legal protection and fraught with danger, armed self-defense was not just a right but the "kingly way" of survival. The firearm was no longer just a tool for hunting or self-defense; it became a powerful cultural symbol of individual liberty, independence, and the ultimate arbiter against any external interference (including government tyranny). The fervent defense of the Second Amendment has its cultural roots here.

The Westward Expansion ultimately achieved America's territorial expansion from the Atlantic to the Pacific, but its most important legacy was cultural rather than geographical. It sowed the seeds of anti-elitism, populism, extreme individualism, and a reverence for firearms in the "Redneck" culture across the vast land. The contemporary "Redneck" demographic's strong distrust of Washington politics and general hostility toward the elite class are clearly linked to the historical traumas of the Westward Expansion. They discovered once again that although they were the heroes of the nation's expansion, they were once again relegated to the status of the "Internal Other" in the new order of law and capital.

Chapter V: The Industrial Wave—From the Nation's Backbone to a Discarded Generation

If the Westward Expansion shaped the political worldview of the "Redneck," then the 20th-century wave of industrialization defined their economic identity and ultimately led to their contemporary predicament. During the economic boom of the two World Wars and the post-war era, millions of rural whites from Appalachia and the South migrated north along the "Hillbilly Highway" to the industrial centers of Detroit, Pittsburgh, Chicago, and Akron. With their spirit of hard work and discipline, they took on the most arduous and dangerous jobs in the automobile, steel, coal, and rubber industries, becoming the core labor force of America's manufacturing explosion.

During World War II, they were the unsung heroes of President Roosevelt's "Arsenal of Democracy," making an immeasurable contribution to the Allied victory. In the golden decades after the war, with the help of powerful unions and stable jobs, they became the mainstay of a vast middle class, creating an era of unprecedented prosperity for the United States. Owning a suburban house, two cars, and a factory job that could support a family was their realization of the "American Dream."

However, the wave of globalization and automation that began in the 1970s and accelerated at the end of the century mercilessly brought this golden age to an end. The technological revolution, centered on digitization, was characterized by a "high-skill bias." It systematically devalued manual, repetitive, and experience-based labor skills while greatly increasing the economic value of abstract, cognitive, and technical skills. The core competencies of the traditional blue-collar worker—physical strength, craftsmanship, and practical experience—could now be replicated with the highest efficiency and lowest cost by algorithms and robots.

Studies show that for every new industrial robot introduced per thousand workers, about six jobs are eliminated, and the wages for the remaining positions are suppressed.

At the same time, globalization made it easy for capital to move factories to countries with lower labor costs. The machines that had once liberated them from the toil of the land now, in a more advanced form, took away their livelihoods. Factories closed on a large scale, and the

"Manufacturing Belt" became the "Rust Belt." This huge drop from national heroes to a discarded generation created a strong sense of deprivation, disillusionment, and an ever-intensifying anger toward the elite class. This process of marginalization was not only economic but also became the most important driver of a fundamental shift in their political allegiance.

Chapter VI: From the Democratic Party to the Republican Party

This history, from the "nation's backbone" to a "discarded generation," has instilled in the "Redneck" demographic a strong sense of nostalgia for a bygone era when hard work and a skilled trade could guarantee a decent and respected life. Their voting behavior can be understood as a delayed protest against historical injustice, driven by the underlying logic: "We gave everything for this country, and you (the political and economic elites) betrayed us." This sense of betrayal was first and foremost directed at the Democratic Party, which had once represented their interests.

During Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" era, the Democratic Party built a formidable political coalition of union labor, Southern whites, farmers, and urban minorities that dominated American politics for a long time. For the industrial workers who formed the "Redneck" base, the Democratic Party provided unprecedented economic security through its support for unions, expansion of social welfare, and large-scale infrastructure projects. At that time, they were staunch supporters of the Democratic Party, viewing it as a shield against the predation of big capital.

However, starting in the 1960s, the internal structure and policy focus of the Democratic Party underwent a fundamental shift. The party's soul gradually shifted from the union and the factory floor to the university campus and the civil rights movement. Its focus moved from universal issues of economic fairness (such as wages and pensions) to cultural and identity issues, such as the anti-Vietnam War movement, racial equality, feminism, and environmentalism. For the traditional white blue-collar class, these new issues were not only alienating but also challenging. Still, they were often seen as a direct challenge to their traditional values, religious beliefs, and existing social status. In the 1970s and 1980s, the rise of environmentalism exacerbated the division.

A series of regulations aimed at protecting the environment was experienced in the coalfields of Appalachia and the industrial towns of the Midwest as hostile policies that killed jobs and threatened their survival. Finally, the Clinton administration's embrace of a globalization agenda in the 1990s, epitomized by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), was, for the

workers of the "Rust Belt," the final, unforgivable betrayal. The party that had promised to protect them from the harshness of the market now actively became an "accomplice" in the outsourcing of jobs.

Feeling doubly abandoned, both culturally and economically, by their former political allies, they became the "Internal Other" within their own party and were ultimately pushed into the arms of the Republican Party. In this historic shift, the Republican Party did not stand idly by. Starting with Nixon's "Southern Strategy," the Republican Party actively designed and implemented a systematic strategy to attract the working-class demographic represented by the "Rednecks":

1. Emphasizing Traditional Values: It made issues such as opposition to abortion and same-sex marriage, and the defense of the family structure, central tenets to appeal to the cultural

conservatism of blue-collar white voters.

2. Forging a "Silent Majority" Identity: It used slogans such as "law and order" and "American renewal" to give a sense of dignity and belonging to a blue-collar class that felt despised by the cultural elites.

3. Exploiting Racial and Class Tensions: Through questioning civil rights policies and criticizing welfare dependency, it cleverly redirected the blame for the loss of social resources to "other immigrant groups" rather than the global flow of capital.

4. Attacking Environmental and Regulatory Policies: It portrayed them as the main culprits in the destruction of coal mining and manufacturing jobs, and attributed the employment difficulties to government regulation, thereby positioning itself as the "guardian of the workers."

Through these measures, the Republican Party gradually transformed from the "party of big business and big capital" to a party with the white working class as one of its core constituencies, becoming the new political home for blue-collar whites.

Chapter VII: Globalization and Anomie—The Elegy of the Forgotten

The economic transformation driven by informatization and globalization since the late 20th century has undoubtedly brought about astonishing productivity gains and undeniable social progress at the macro level, but at the micro level, it has inflicted a devastating catastrophe on a portion of the American blue-collar working class.

According to David Ricardo's theory of "comparative advantage," globalization, through international division of labor and trade, can achieve an optimal increase in global social welfare. However, the real-world practice of this classical economic theory has shown that its benefits and costs are extremely unevenly distributed. Labor-intensive manufacturing was massively outsourced to low-cost countries, allowing American capital and high-tech industries to reap enormous benefits from globalization. In contrast, for the workers of the "Rust Belt," globalization was not the "win-win" scenario of the textbooks but the harsh reality of factory closures, mass unemployment, and community decay.

For a long period of history, their plight received insufficient attention from the media and was not effectively addressed by policy, leaving them the forgotten people in the narrative of "progress." J.D. Vance's memoir, Hillbilly Elegy, profoundly reveals the phenomenon of "collective decline" of this specific group. Drawing on the theory of "anomie" by the sociologist Émile Durkheim, it is not difficult to see how economic deprivation can transform into psychological disorder and despair. When the economic foundation, social norms, and value system on which a community depends are destroyed by external forces, and a new system is not established, people fall into a state of rootlessness, disorder, and hopelessness. This state of "anomie" manifests itself in a series of self-destructive social behaviors: opioid abuse, alcoholism, family breakdown, and a surge in suicide rates, known as "deaths of despair."

This thesis argues that these so-called "pathologies" are not entirely due to the inherent moral defects of this group, but rather are symptoms of the despair that arises when their economic foundation, social status, and cultural dignity are systematically hollowed out. This pervasive despair and resentment ultimately became the most fertile ground for breeding extreme politics and social unrest.

Chapter VIII: Equality vs. Equity

America's diversity policies, from the "Affirmative Action" of the 1960s to the recent DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) initiatives, are primarily aimed at correcting historical systemic injustices and supporting traditionally disadvantaged social groups. However, these policies have, in practice, created a profound philosophical paradox: to ultimately achieve a "color-blind" ideal society, they first require the recognition and large-scale use of race and identity as criteria for distributing opportunities.

This core contradiction has sparked a fierce clash in American society between two fundamental conceptions of "fairness." Procedural Fairness (Equality of Opportunity) is a core concept rooted in the American founding spirit. Its central idea is that the government's duty is to ensure that everyone starts at the same line in a competition and abides by the same set of rules for everyone. This perspective emphasizes equality in the competitive process, not equality of outcomes. It is deeply rooted in the spirit of individualism and the belief in "meritocracy," that an individual's success or failure should be determined entirely by their own talent, character, and effort. Any preferential treatment based on race, gender, or other identity markers is seen as a corruption of this fair process.

For many who subscribe to this belief, policies that emphasize equality of outcomes constitute "reverse discrimination." Equity (Substantive Fairness). In direct opposition to procedural fairness is equity, or substantive fairness. This view holds that if the starting lines of the competitors are inherently different—due to centuries of slavery, racial segregation, and systemic discrimination—then no matter how fair the rules of the game, the final outcome will inevitably be unfair. It focuses not only on equality of opportunity and rules but also on the substantive fairness of the outcome. Therefore, to achieve this goal, society needs to actively intervene administratively to compensate for the inequality of the starting points. For example, by giving certain disadvantaged groups a "thumb on the scale" or "preferential treatment" in

college admissions, career promotions, and government contract allocation, to counter the structural disadvantages caused by history. In the logic of equity, this intervention is not a violation of fairness but the necessary means to achieve true fairness.

For the "Redneck" demographic, their worldview is firmly grounded in the principles of procedural fairness and meritocracy. They believe that hard work and following the rules should be rewarded. However, in reality, they feel that their beliefs are being betrayed. In college admissions and career promotions, they or their children's opportunities may be taken away by a more diverse but, in their view, less qualified competitor due to diversity policies.

In government contract bidding, small businesses may lose out on opportunities they should have won on merit due to "set-aside" mechanisms. This feeling is filled with frustration and a sense of injustice, which has converged into a strong sentiment of "reverse discrimination" and has become one of the most complex and acute contradictions in American society. This once again confirms that for groups rooted in two different sets of first principles, even the definition of the word "fairness" is oppositional.

Chapter IX: The Misunderstood "Unconditional Support"

A Sociological Analysis of the Trump Exemption: Donald Trump's political career is a classic of the unconventional. He has systematically challenged the boundaries of fact, logic, morality, and social ethics, yet has always miraculously transformed huge controversies into "fuel" for the further loyalty of his supporters. Whether it was the "Stormy Daniels" "hush money" case, the defamation lawsuit by the famous writer E. Jean Carroll, the multiple bankruptcies and zero-tax records in his business career, or the countless untrue, absurd, and even arrogant statements he made during his presidency, nothing has truly shaken his solid political base.

Outside observers often attribute this to a baffling and blind "unconditional support." However, this support is not truly "unconditional" but is rooted in a political alliance of "Redneck" grassroots, evangelical voters, and some Republican elites. This alliance, with its unique psychological mechanism, reinterprets all of Trump's "problems."

Drawing on the theory of "charismatic authority" by the German sociologist Max Weber, we can better understand this phenomenon. Charismatic authority does not depend on tradition (such as monarchy) or legality (such as bureaucracy) but is entirely based on the followers' conviction in the leader's extraordinary personal charm. In the eyes of the followers, the leader is endowed with superhuman qualities, and conventional rules and morals do not bind his words and actions.

Within this framework, Trump's business disputes are not seen as fraud or failure but as proof of his shrewdness and ability to use the "corrupt rules made by the establishment" for his own benefit. His sexual "scandals" are downplayed as trivial personal matters, "mistakes any man could make," and are far less serious than the threat to national security posed by Hillary Clinton's "emailgate." His unfiltered, outlandish remarks, on the other hand, are seen as the "authenticity" of a leader who dares to speak the "emperor's new clothes" truth, in stark contrast to those politicians who are smooth-tongued but insincere.

Trump offered this vast, forgotten, and despised group what they craved most: a brave spokesperson and a fearless fighter. He affirmed their value in the most direct language and attacked their "enemies" (the media, academia, globalists) with the most aggressive posture. In return, this group provided him with a "bulletproof wall" against all negative attacks, granting him a privilege to ignore the rules, an "exemption."

Therefore, Trump's "political willfulness" was not something that fell from the sky but was based on a "wartime exemption" granted by his supporters. This exemption stems from a consensus: to win this "war" for their dignity and survival, their leader must be allowed to use all

"unconventional weapons." His supporters see every "outrageous" act by Trump as an act of fighting for them. Based on this deeply intertwined symbiotic relationship, they are naturally willing to become his most solid political fortress.

This "exemption," based on identity and emotional bonds, allows a political leader to transcend the constraints of facts, law, and even traditional morality, which not only reshapes the rules of the political game but also poses an unprecedented challenge to the foundation of democracy—accountability.

Chapter X: The Price of Progress

The profound economic transformation that the United States has undergone since the late 20th century has undoubtedly been "progress" at the macro level. However, behind this progress lies a profound paradox. The theory of "creative destruction," proposed by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter accurately describes this internal contradiction. Schumpeter believed that the essential driving force of capitalism is a process of constantly revolutionizing the economic structure from within, that is, constantly destroying the old and creating the new. The rise of new technologies, new industries, and new business models is necessarily accompanied by the elimination and destruction of old structures. This is a painful but necessary process that drives economic development and optimizes resource allocation. The rise of Silicon Valley and the establishment of global supply chains both attest to the powerful explanatory power of this theory.

However, the problem is that when this "destruction" is disproportionately, long-term, and systematically borne by specific groups of people and regions, the social contract is in danger of being torn apart. According to social contract theory, citizens cede some of their individual rights to the state in exchange for overall protection and well-being. When the development of the country (i.e., "progress") systematically harms the well-being of a portion of its citizens, the state has an undeniable responsibility to compensate and assist them.

This is not just a matter of humanitarian compassion but a necessary measure to uphold social justice and collective identity. If the sacrifices of one group are taken for granted as a "price," then the cohesion of society will be completely lost. Anyone could become the next "discarded" group, leading to a pervasive sense of insecurity throughout society, ultimately eroding the foundations of progress. In the past few decades, the American elite class has largely embraced the "creation" in "creative destruction" while selectively ignoring the consequences of its "destruction." Retraining programs for workers in the "Rust Belt" have often been superficial, and the strength of the social safety net has been far from sufficient to cope with such a large-scale industrial transfer.

Therefore, properly handling this issue is crucial to consolidating the social contract, ensuring that the fruits of development can be more widely shared, and making "progress" truly beneficial to all. The core idea is not to obstruct progress but to manage its costs. When a society cannot properly manage the costs of progress, it is not surprising that those groups crushed by progress will eventually choose a leader who promises to "turn back the clock."

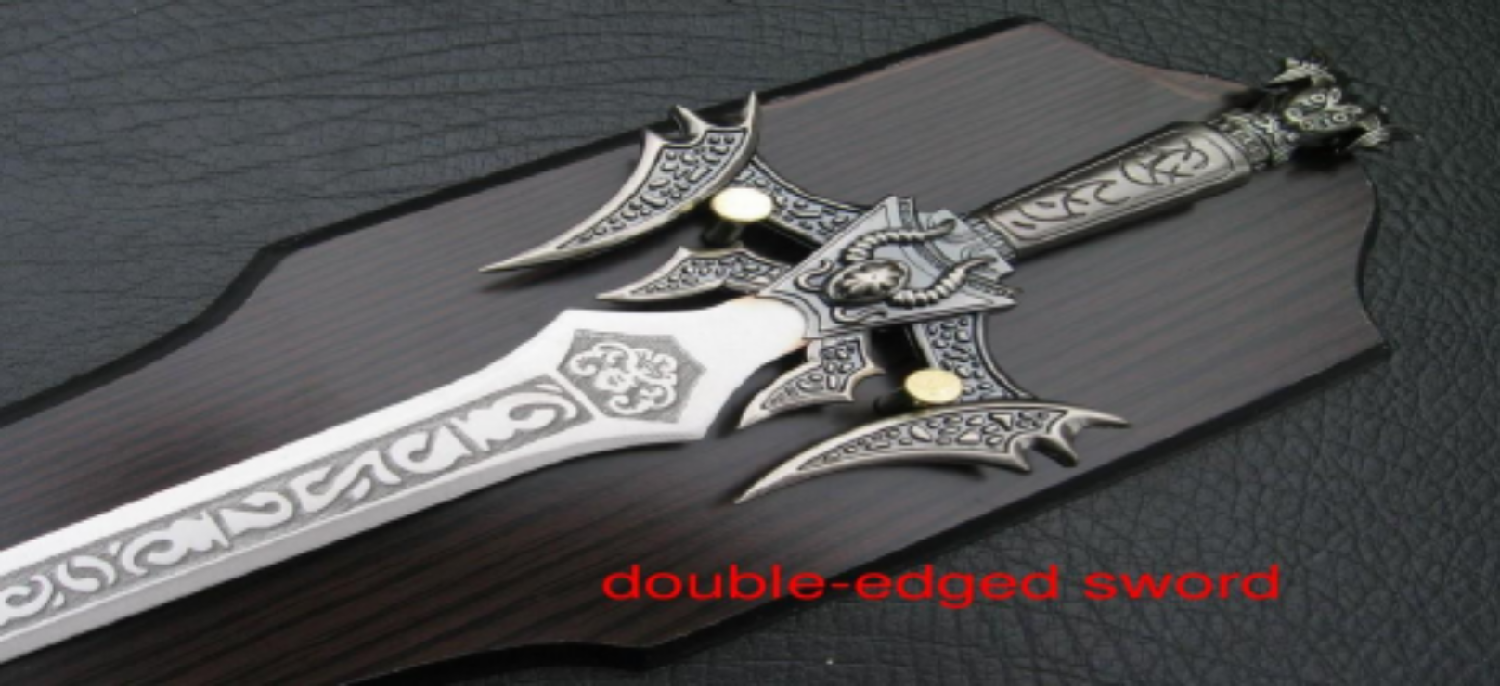

Chapter XI: A Double-Edged Sword

The Mobilization Art of Trumpism and Its Destructive Legacy Donald Trump's personality is extremely extroverted, confident, and flamboyant, and he thrives on being the center of attention. He is a natural performer who has transformed the political stage into his personal reality show. His style is highly confrontational, launching personal attacks on any critic. He is unpredictable, able to quickly change his position or strategy according to the situation, making it difficult for both opponents and allies to grasp.

However, beneath this seemingly changeable style, Trump's core political views—nationalism centered on "America First," trade protectionism, a hardline immigration policy, and a deep distrust of the establishment—have shown surprising consistency and stability since his youth. These views are not derived from a complex theoretical system but are more based on his long-term personal intuition, business experience, and keen sense of public sentiment.

The Sharp Edge of the Sword:

Powerful Political Mobilization. The sharp edge of Trump's political artistry lies in his success in uniting and transforming the disappointment and anger of millions of people into a powerful and subversive political force. The MAGA movement has now become a prairie fire, and there are successors to carry it on. The Republican Party has shown a high degree of unity, forming a strong, cohesive force around Trump. Moreover, conservatives now hold a solid majority on the Supreme Court and have significant influence over the judicial system at all levels. Trump not only launched a political movement but also completely reshaped the entire Republican Party. He shifted the party's focus from a traditional conservative agenda (such as small government and free trade) to a new direction centered on populism and nationalism, and in the process, demonstrated an unparalleled ability to mobilize the party's base voters.

The Other Edge of the Sword:

Deep Social Division. However, the other edge of this sword has cut deeply into the fabric of America. Its negative impact is mainly reflected in three aspects:

1. Societal Fragmentation: Trump's mobilization logic is essentially a form of "identity politics." By constantly reinforcing the "us vs. them" opposition, he has transformed political differences from negotiable "policy disputes" to irreconcilable "identity wars." While this strategy can greatly consolidate his own camp, it comes at the cost of national unity, destroying the traditions of bipartisan cooperation and political compromise.

2. The Oversimplification of Politics: By attributing all complex socio-economic problems to external enemies (such as China and Mexico) or internal traitors (such as the "deep state" and disloyal Republicans), this approach, while easy to disseminate and understand, has fundamentally disabled society's ability to solve problems collaboratively. Society has been dragged into a "zero-sum game" state, where one side's victory is necessarily the other's defeat. Politics is no longer the art of seeking consensus but has devolved into a naked power struggle.

3. The Annihilation of Fact: Trump's campaign strategy, including the repeated use of "fake news," accusations of "witch hunts" by opponents, and "alternative facts," has systematically blurred the line between fact and fiction. He has successfully convinced his supporters that their "feelings" are more important than objective facts and that his words are more credible than the mainstream media. When "what is fact" itself can be disputed and denied in a society, the rational debate, media supervision, and judicial fairness on which a democratic system depends lose their foundation. This is known as an "epistemic crisis." The most lethal harm of this double-edged sword is that it has dismantled the ability of members of society to share a common reality. In a country where even basic facts need to be debated, rebuilding consensus and trust, and repairing a deeply torn society will be America's most formidable challenge in the future.

Chapter XII: The Presidential Paradox

The Glory and Alienation of an Ethnic In the grand narrative of American national history, immigrants from Scotland and Ireland are an indispensable chapter. Their descendants, especially the Scots-Irish mentioned earlier, have injected a spirit of resilience, love of freedom, and independence into the American soul. The profound influence of this ethnic group on American politics can be summed up by a startling fact: of the 47 presidents of the United States to date, as many as 31 have a clear Scottish or Irish ancestry. This overwhelming proportion eloquently demonstrates the central role of this ethnic group in the American power structure.

From the founding father Andrew Jackson to the 19th-century definer James K. Polk, from the 20th-century figures of Woodrow Wilson and Harry S. Truman to the modern icons of John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan, and more recently, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and even Donald Trump, these names trace a living history of the United States.

This raises a profound paradox: why has the vast grassroots of an ethnic group that has produced more than two-thirds of America's presidents come to feel an unprecedented sense of dispossession and marginalization today? The answer lies in the fact that significant class differentiation has long existed within the Scots-Irish. The presidents, generals, entrepreneurs, and elites are the upper class of this ethnic group who have successfully integrated into and mastered the rules of the "Establishment." Many of them, through higher education, law, or business, have successfully transitioned from the "individual sovereignty" culture of the frontier to the "social contract" world of the establishment. Andrew Jackson himself is a perfect example of this transition: he was a typical frontier fighter who eventually became the supreme master of federal power.

The "Redneck" culture, on the other hand, represents the vast grassroots that remained in the Appalachian Mountains and the "Rust Belt," unable or unwilling to complete this class advancement. Their anger is directed not only at external elites but also implicitly contains complex feelings toward the successful members of their own ethnic group—a feeling of being "abandoned by their own kind." Therefore, the glorious presidential history of the Scots-Irish, far from soothing the anxieties of the contemporary "Redneck" community, has cruelly intensified their sense of loss. The huge contrast between the glory of their ancestors and their own plight has created a powerful historical memory of "we should be the masters of this country," which is precisely the deepest source of their sense of "betrayal."

Chapter XIII: The Future of MAGA

The Succession and Challenge of Charismatic Authority. The economic decline, community disintegration, and cultural loss experienced by the grassroots working class represented by the "Rednecks" is a deep and poignant elegy of our time. Donald Trump, with his inimitable political magic, has transformed this elegy into a powerful force that has shaken the foundations of American politics, namely, the burgeoning MAGA movement. As mentioned earlier, Trump's power is entirely based on his "charismatic authority." This authority is a political asset that cannot be easily replicated or passed on. It bypasses traditional media and political intermediaries to establish a direct, almost fanatical, emotional connection with his supporters.

However, the risks of this model are obvious: its vitality is entirely dependent on the leader's own existence. Once Trump fades from the political scene for any reason, the movement may

quickly fall into a "leadership vacuum" and face the danger of collapse. The rise of J.D. Vance, however, heralds another possibility for the MAGA movement, namely, the "institutionalization of Trumpism." Vance himself is a symbol full of meaning: he comes from the "Redneck" community but graduated from Yale Law School, which enables him to articulate an anti-elite philosophy in the language of the elite. He represents an effort to transform "Trumpism" from a sensual intuition and personal charm into a replicable and heritable political philosophy. Vance's goal is to transform MAGA from a movement driven by an individual into a lasting institution with its own theoretical ideas (such as nationalist economics and confrontational political strategies), organizational structure (think tanks, media networks), and long-term vitality. He seeks to provide a more coherent and defensible theoretical framework for the anger and grievances of the "Redneck" community.

The challenge for the Vance model is that if the movement becomes too theoretical and strategic, it may lose its grassroots passion and vitality in the process. However, regardless of who is in charge, the deep structural fissures in American society that the MAGA movement has revealed—the gap between the winners and losers in the process of informatization, globalization, and diversification; the economic, technological, and cultural divide between the coastal metropolises and the vast rural areas of the Midwest; and the deep distrust of the "Redneck" community toward political, economic, media, and academic elites—will persist for a long time. Therefore, the MAGA movement itself is nothing more than the politicized expression of these deep-seated fissures at a specific historical moment. Even if Trump leaves the stage, even if the banner of MAGA changes, this huge political energy that has been released and the social fault lines that have been exposed behind it will continue to exist in the foreseeable future. future and will reshape the American political landscape in various forms.

In conclusion, this book is not just a historical account of the "Redneck" demographic; it is a philosophical inquiry into the soul of America itself. From the frontier to the Revolutionary War, from industrialization to globalization, this group has played the dual role of contributor and victim at every stage of the nation's development, thus forging a unique cultural DNA. Trump's political rise was no accident; it was the concentrated outbreak of this historical accumulation. More fundamentally, this history highlights the eternal conflict between two irreconcilable first principles within American society:

1. The Establishment Principle (based on the Social Contract):

• View of Government: The state and society are rational communities established based on a "social contract," and the government is the necessary framework for maintaining order and promoting collective well-being.

• View of Liberty: Liberty is a right exercised within the framework of law and order; it is an orderly liberty.

• View of Fairness: It leans toward "equity," acknowledging and striving to correct inequalities caused by history and social structures.

• View of Property: Property rights are protected by law, but the government can regulate, tax, or expropriate them for the public good.

2. The Principle of Individual Sovereignty (based on the supremacy of individual rights):

• View of Government: The individual is a sacred and inviolable ultimate sovereign unit, and the government is a "necessary evil" established to protect their existing rights, and its power must be strictly limited.

• View of Liberty: Liberty is the absolute right to be free from external (especially governmental) coercion and interference; it is self-governance.

• View of Fairness: It strictly adheres to "equality of opportunity," and any preferential treatment based on identity is considered "reverse discrimination."

• View of Property: Property rights are natural rights derived from labor and possession, sacred and inviolable, and the government's primary duty is to protect, not interfere with them.

It is these two irreconcilable starting points that lead to the inevitable clash between the two camps on all key issues. When one side discusses how to achieve broader social fairness through institutional design, the other side sees this very act as a fundamental violation of individual liberty and procedural fairness. Their dialogue is often ineffective because, although they use the same words (such as "liberty" and "fairness"), these words are defined by two completely opposite systems of axioms. This conflict is not a simple dispute of interests but a fundamental conflict between two incompatible worldviews.

In summary, the severity of social division in the United States stems from the fact that the conflict originates not at the policy level but at the axiomatic level. When disagreements arise from interests, they can be resolved through negotiation and compromise, but when they stem from beliefs and first principles, compromise means betraying one's own worldview and thus becomes almost impossible. The real challenge has transcended a typical political crisis and has evolved into a profound philosophical dilemma. Therefore, understanding the history of the "Rednecks," intertwined with glory and rage, is no longer just the key to deciphering the rise of Trump. It is a mirror that reflects the deep fissures in the American soul, seriously questioning whether the collective identity of this republic can still be maintained and how it can be maintained. The value of this book lies in its unique and profound historical and sociological perspective on one of the most dangerous core challenges of our time.

If you find any issues in this article, please contact Dr. Lee at john@pacificspan.com or (480) 882-8015.